Previous posts in this series:

Hume 1: Conventions

Hume 2: Justice

This post will cover Hume’s theory of moral judgment. I will follow Geoffrey Sayre-McCord’s interpretation of that theory, which can be found in a paper called “On Why Hume’s ‘General Point of View’ Isn’t Ideal – and Shouldn’t Be.”[1]

Moral Sentiments

Hume begins the Treatise with the claim that all our ideas are derived from sense experience. This includes the ideas of virtue and vice, good and bad, right and wrong. However, he argues that these moral ideas are not derived from the external senses, such as sight and touch. Rather, they are derived from our internal senses, that is, from our sentiments, feelings, and emotions. Certain sentiments – for example, resentment and outrage, or admiration and appreciation – have a “distinctive qualitative feel” that marks them out as moral sentiments.[2] These sentiments are the source of our moral ideas in the same way that visual and tactile sensations are the source of our ideas of shape, size, and color.

Hume thinks that moral sentiments only arise under certain circumstances. To be specific, he thinks that they only arise when we take “the general survey.”[3] Taking the general survey means setting aside self-interest and focusing instead on the “interest or pleasure…of the person himself, whose character is examin’d; or that of persons, who have a connexion with him.”[4] When we take the general survey, our capacity for sympathy engages us with the interests of the people that we are focused on. We feel outraged when they are harmed, and we feel appreciative when they receive help, even though our own interests are not directly affected. These sentiments, the sentiment that arise when we set aside self-interest and allow ourselves to sympathize with other people, have a distinctive qualitative feel that unites them as a group and marks them out as moral sentiments.

Although he thinks that moral ideas are derived from moral feelings, Hume recognizes that we do not always feel what we ought to feel. Sometimes people feel appreciative when they should not, and sometimes people do not feel appreciative when they should. In the next two sections, I will discuss the way that Hume distinguishes what we do feel from what we ought to feel.

Correcting for the Influence of Vividness, Distance, and Fortune

Often, two people feel differently about the same situation. This sometimes happens even though both people take the general survey when they view the situation. That is, sometimes two people feel differently about the same situation even though both people (1) set aside their own interests and (2) allow themselves to sympathize with the people who are directly affected by the situation under consideration.

For instance, the way that a subject is presented often affects the way that people feel about it. An engaging, vivid presentation is likely to garner a more passionate response than a dry recounting of the facts. Say that Jones and Smith both hear about a devastating earthquake that occurred on the other side of the world. Although their own interests are unaffected by the disaster, they both sympathize with the people who were affected. How strongly they sympathize, however, is likely to depend in part on how they heard about the earthquake. If Jones watched an engaging news report, and Smith read a tedious government account of the death toll and the economic damage, Jones is likely to sympathize more strongly.

Although “vividness of presentation,” as Sayre-McCord calls it, affects our sentiments, we recognize that it should not be allowed to distract from the substance of the issues.[5] Accordingly, we control for the influence of vividness when we make moral judgments. Both Jones and Smith know that, whether you hear about it through a vivid news report or a tedious government account, the damage done by the earthquake is equally bad. Accordingly, if they have a conversation about the scale of the disaster, they will ignore the effect that vividness of presentation has on their sentiments.

Vividness is not the only factor that we control for when we make moral judgments. Hume thinks that we control for the influence of distance and fortune as well.[6] He uses the following example to illustrate the way that we correct for the influence of distance:

A statesman or patriot, who serves our own country in our own time, has always a more passionate regard paid to him, than one whose beneficial influence operated on distant ages or remote nations; where the good, resulting from his generous humanity, being less connected with us, seems more obscure, and affects us with a less lively sympathy. We may own the merit to be equally great, though our sentiments are not raised to an equal height, in both cases. The judgement here corrects the inequalities of our internal emotions and perceptions…

EM Section V Part II Paragraph 26

Typically, we feel more appreciation for a statesman whose good work benefits our friends, family, and countrymen than a statesman whose work benefits distant strangers. However, we recognize that, when we assess the merits of the two statesmen, we should not allow this personal connection to bias our judgment. Accordingly, we control for the influence that distance has on our sentiments when we assess merits of the two statesmen.

The influence of fortune on sentiment is felt when, by sheer luck, intentions and outcomes do not align. For example, suppose that your friend Allison intends to help you but inadvertently ends up doing you harm. You are unlikely to feel as appreciative as you would have if things had worked out the way she intended. Still, if you are asked to say whether Allison is generous and quick to help others, you will not hold her bad luck against her. You will give an answer that focuses on Allison’s intentions, not the outcomes of her actions, susceptible as the latter are to the influence of fortune.

To summarize, Hume thinks that, when we make moral judgments, we ought to control for the influence that vividness, distance, and fortune have on our sentiments. If we do not, we will have a hard time reaching agreement about what is good and bad, right and wrong, virtuous and vicious. If we allow vividness, distance, and fortune to influence our moral judgments in the same way that they influence our moral sentiments, we are liable to make irreconcilably different judgments about the same situation.

The General Point of View

Like many philosophers, Hume values objectivity. In his opinion, we ought to take up an objective, unbiased point of view when we make moral judgments. His name for this perspective is the ‘general point of view.’[7] The general point of view is the perspective that we take up when we control for the influence that vividness, distance, and fortune have on our sentiments.

Hume thinks that, for moral sentiment S, and for circumstances C, it is appropriate to feel S in response to C if and only if an occupant of the general point of view would feel S in response to C. In other words, Hume appeals to the general point of view to distinguish between what we do feel and what we ought to feel. Oftentimes, what we do feel is influenced by vividness, distance, and fortune. What we ought to feel is what we would feel if we were not influenced by these things.[8]

Hume illustrates this point by drawing an analogy with vision:

The same object, at a double distance, really throws on the eye a picture of but half the bulk; yet we imagine that it appears of the same size in both situations; because we know that on our approach to it, its image would expand on the eye, and that the difference consists not in the object itself, but in our position with regard to it.

EM Section V Part II Paragraph 26

Because distant objects appear to be smaller, we control for distance when we make judgments about size. This allows us to draw a distinction between experiencing the impression that an object is small and judging that it actually is small.

Similarly, we recognize a distinction between feeling a moral sentiment and judging that it is appropriate to feel that sentiment. Our feelings depend in part on vividness, distance, and fortune. When we ask whether our feelings are correct, we turn to the general point of view.

The Role of the General Point of View

When we make moral judgments, we set aside the “point of view, which is peculiar to us” in favor of the objective general point of view.[9] When we do so, we are required to set aside some of our own interests. What reason do we have, then, to take up the general point of view? Hume’s answer is that doing so allows us to avoid problems that we would otherwise face:

We are quickly oblig’d to forget our own interest in our judgments of this kind, by reason of the perpetual contradictions, we meet with in society and conversation, from persons that are not plac’d in the same situation, and have not the same interest with ourselves.

T 3.3.3.2

It is unworkable for each of us to judge moral matters from our own peculiar point of view. If we did, too many disputes would arise. In order to avoid conflict, we need a generally recognized impartial standard that can be used to adjudicate disputes. The general point of view provides such a standard.[10]

Which Point of View is the General Point of View?

Hume describes the general point of view as the perspective that we take up when we control for the influence of distance, vividness, and fortune.[11] It is worth noting, however, that this description does not specify one unique point of view. More than one point of view satisfies this description because there is more than one way to control for the influence of distance, vividness, and fortune. In order to illustrate this point, I will return to Hume’s statesman example.

A generous, self-sacrificing statesman can expect to be deeply appreciated by the people who live in his own time and country. It is understandable if the next generation of his countrymen appreciate him somewhat less, seeing as they are somewhat removed from the benefits of his good work. The subsequent generation will be even further removed, and no one will be surprised if they feel even less appreciation.[12]

Although the appreciation that we feel for a selfless statesman varies depending on our distance from him, our judgments about his character need not. We are capable of controlling for the influence of distance when we make judgments about merit. In this way, members of different generations can reach agreement about the character of a statesman.

Still, what position should they agree on? There are a number of options. They might agree that a statesman should be judged from the point of view of his contemporaries, or from the point of view of the following generation, or the generation after that. The first option requires members of the second and third generations to set aside their peculiar points of view in favor of the point of view of the first generation. The second option requires members of the first and third generations to take up the point of view of the second generation. Finally, the third option requires members of the first and second generations to defer to the point of view of the third.

Each of the three options represents a different way of controlling for the influence of distance. In order for the members of the different generations to reach agreement, they need to pick one of the three options. The issue is important because each of the three options generates a different result. Because the statesman’s contemporaries can be expected to appreciate him more than members of later generations, the first option will result in a more complimentary assessment of his merits than the other two. The second option will result in a less complimentary assessment than the first, and the third option will result in the least complimentary assessment of the three.

As this example illustrates, there is more than one way to control for the influence of distance, vividness, and fortune. For this reason, it is fair to ask Which way should we pick? In other words, Which point of view is the general point of view? To my knowledge, Hume does not address this question directly.[13] However, a clue to how he would answer it can be found by returning to his theory of justice.

Recall Hume’s answer to the question How should property rights be distributed? His opinion is that the just person will comply with whatever scheme of property rights happens to be in place, so long as (1) that scheme is mutually beneficial and (2) other people can be expected to comply as well. The just person will do so because (a) the institution of property is a convention and (b) the just person has a “commitment to conform to general rules established by conventions, given that the conventions are mutually advantageous, and that others are doing their share as well.”[14]

A similar answer can be given to the question Which point of view is the general point of view? Moral people, the answer goes, have the same “commitment to conform to general rules established by conventions, given that the conventions are mutually advantageous, and that others are doing their share as well.” The general point of view establishes a standard that can be used to adjudicate disputes. If it is appropriate to see this standard as a general rule established by convention, then moral people will comply with whatever standard happens to be generally accepted, so long as (1) it is mutually beneficial and (2) other people can be expected to comply as well.[15]

What remains is to determine whether it is appropriate to see the standard established by the general point of view as a general rule established by convention. It turns out to be a complicated matter, however, to determine whether this is the case.

Morality as a Convention?

In Hume 1, I highlighted five features of conventions: mutual benefit, multiple solutions, different preferences, unplanned agreement, and reciprocal performance. In order to determine whether it is appropriate to see the standard established by the general point of view as a general rule established by convention, we need to determine whether it exhibits these five features. Complications arise, however, before we get past the first one.

Recall that, in the context of justice, Hume argues that property rights make a peaceful and orderly society possible. The alternative is a state of “universal license.”[16] Each person is better off in a peaceful and orderly society than they would be in a state of universal license, so long as the order in question is just.

Similarly, the general point of view makes a “harmonious social life” possible by providing us with a standard that can be used to adjudicate disputes.[17] If each person is better off living in a harmonious society than they would have been in a state of “perpetual contradictions,” then morality is mutually beneficial. It is a complicated matter, however, to determine whether this is the case.

In order to appreciate the complications that are involved, consider an example. Suppose that we live under moral code M. That is, M is the standard that we use to adjudicate disputes over moral matters. Suppose that there is a dispute over whether each person is better off living under moral code M than they would have been in a state of perpetual contradictions. Welfare is a moral matter, so this dispute is over a moral matter.[18] In order to resolve the dispute, then, we ought to refer to M itself. This is a strange situation that I hope to explore more fully in future posts. I will reserve judgment on the question of whether it is appropriate to see the standard established by the general point of view as a general rule established by convention until after I do so.[19]

It is worth registering the reason why the same sort of complication does not arise in the context of justice. Suppose that property rights are distributed according to distribution P. Further suppose that there is a dispute over whether each person is better off under P than they would have been in a state of universal license. Welfare is a moral matter, so, in order to resolve the dispute, we ought to refer to M. We do not need to resolve a dispute over P by referring to P itself.

[1] Sayre-McCord, G. (1994). On Why Hume’s “General Point of View” Isn’t Ideal – And Shouldn’t Be. Social Philosophy and Policy, 11(1), 202-228.

[2] See “Isn’t Ideal” footnote 22 on page 209.

[3] At T 3.3.5.1 Hume says “the pain or pleasure, which arises from the general survey or view of any action or quality of the mind, constitutes its vice or virtue, and gives rise to our approbation or blame.” Sayre-McCord writes “the distinctively moral sentiments that call for correction come in the first place, Hume says, ‘only when a character is considered in general, without reference to our particular interest’” (“Isn’t Ideal” 209). Here Sayre-McCord quotes T 3.1.2.4.

[4] T 3.3.1.30

[5] “Isn’t Ideal” Section III Paragraph 3

[6] “To explain why it is that our judgments do not vary along with these sentiments, Hume notes that we control for the effects of distance, vividness, and fortune, on sympathy…” (“Isn’t Ideal” 210).

Also, according to Sayre-McCord, Hume thinks that we control for ignorance as well. On page 203 of “Isn’t Ideal,” Sayre-McCord writes “Hume does identify and defend a standard of moral judgment…that controls for ignorance.” However, it seems that controlling for ignorance is just a consequence of controlling for fortune. Ignorance, so long as it is not culpable ignorance, is just a matter of luck. For this reason, I do not distinguish in the main text between controlling for ignorance and controlling for fortune more broadly.

In addition, Hume says that “all sentiments of blame or praise are variable…according to the present disposition of our mind” (Treatise 3.3.1.16). Because “present disposition of our mind” is fairly similar to vividness, I have not devoted a separate discussion to it.

[7] “…we fix on some steady and general points of view; and always, in our thoughts, place ourselves in them, whatever may be our present situation.” (T 3.3.1.15) Sayre-McCord explains that “Hume talks of general points of view here, rather than of the general point of view, because the problem he is pointing out is not unique to morality but arises ‘with regard to both persons and things.’ In different areas, different points of view will be relied upon…” (“Isn’t Ideal” Page 216 Footnote 32).

Note that taking the general survey and taking the general point of view are two different things. Sayre-McCord emphasizes this point in “Isn’t Ideal.”

[8] Hume far from the only philosopher who thinks that we ought to take up an objective point of view when we make moral judgments. As Sayre-McCord emphasizes, however, he differs from other philosophers in the way that he characterizes the point of view that he thinks is appropriate for the task. Hume is not, as many other philosophers are, an ideal observer theorist. That is, Hume does not think that the appropriate point of view is that of an imaginary “observer who enjoys, and response equi-sympathetically in light of, full information about the actual effects on everyone of what is being evaluated…” (“Isn’t Ideal” 204). This is the main thesis of Sayre-McCord’s “On Why Hume’s ‘General Point of View’ Isn’t Ideal – and Shouldn’t Be.”

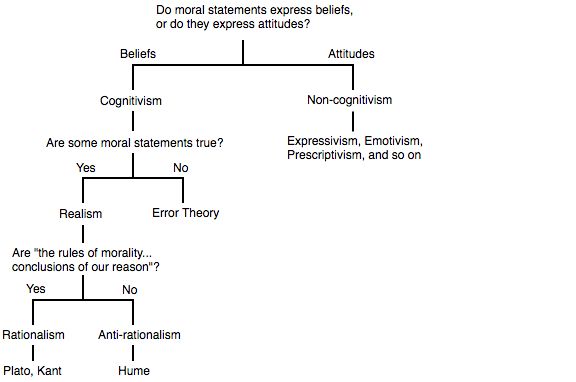

Because of the emphasis that he places on sentiment, Hume is often seen as a non-cognitivist. In footnote 6 of “Hume on Practical Morality and Inert Reason,” Sayre-McCord lists Jonathan Harrison, Barry Stroud, and J. L. Mackie as interpreters who read Hume this way. In contrast, on Sayre-McCord’s reading, Hume is committed to cognitivism. There is a fact of the matter about how an occupant of the general point of view would react to a given circumstance. The general point of view sets a standard, then, that can be used to determine whether moral claims are true or false. Because he thinks that this determination can be made, Hume is a cognitivist.

[9] Treatise 3.3.3.2

[10] Hume also claims that “indeed ’twere impossible we cou’d ever make use of language, or communicate our sentiments to one another, did we not correct the momentary appearances of things, and overlook our present situation” (Treatise 3.3.1.16). This is another role that the general point of view plays.

[11] See footnote 6.

[12] Obviously, this example is somewhat contrived. The members of a generation may not all feel the same way. The reputation of statesman who is reviled in his own time may improve after he dies. I have ignored these and other possibilities in order to create a suitable example. A suitable example changes only one variable at a time. In real world situations, many variables change at a time. For this reason, philosophical examples are often somewhat contrived.

[13] He gets close in the piece titled “A Dialogue.”

Also, Hume’s discussion of the “narrow circle” condition might seem to answer the question. I have in mind passages such as: (1) We “confine our view to that narrow circle, in which any person moves, in order to form a judgment of his moral character” (Treatise 3.3.3.2), (2) “The only point of view, in which our sentiments concur with those of others, is, when we consider the tendency of any passion to the advantage or harm of those, who have any immediate connexion or intercourse with the person possess’d of it” (Treatise 3.3.3.2), and (3) Taking the general survey requires focusing instead on the “interest or pleasure…of the person himself, whose character is examin’d; or that of persons, who have a connexion with him” (T 3.3.1.30).

These passages might seem to suggest that, when we evaluate a person’s character, we ought to (and usually do) take up the point of view of people who have a close connection to that person. However, I think that this is not the way that these passages should be understood, for three reasons:

First, it is not plausible that, when we evaluate a person’s character, we ought to (and usually do) take up the point of view of people who have a close connection to that person. To believe this is to believe that, in moral matters, people who have a close connection to the person under evaluation have the final word. But no one believes this. On the contrary, we sometimes say “you’re biased because you’re too close to the issue.”

Second, Hume says that “when the natural tendency of [a man’s] passions leads him to be serviceable and useful within his sphere, we approve of his character” (Treatise 3.3.3.2). He does not need to be serviceable and useful to everyone in the world (and to future people too) in order for his character to secure our approval. This would be too high a bar. It would be too high a bar because “the generosity of men is very limited, and that it seldom extends beyond their friends and family, or, at most, beyond their native country. Being thus acquainted with the nature of man, we expect not any impossibilities from him” (Treatise 3.3.3.2). If this is Hume’s grounds for imposing the narrow circle condition, it does not require him to hold the position that the correct way to evaluate a person’s character is to take up the point of view of people who have a close connection to that person. He can maintain instead the more plausible position that our evaluations should be based on the effects that the character traits of the person under evaluation tend to have on people within the narrow circle. This leaves room to specify some other point of view – besides that of people who have a close connection with the person under evaluation – as the correct point of view to take up when we evaluate character, so long as this point of view focuses on the effects that the character traits of the person under evaluation tend to have on people within the narrow circle. This more plausible view does not expect an impossibility from the person under evaluation because that person is only expected to have a serviceable and useful influence on those around him, not on everyone in the world (and future people too). Because no impossibility is expected, this more plausible view squares with the grounds for imposing the narrow circle condition.

Third, even if Hume believes that, when we evaluate a person’s character, we ought to take up the point of view of people who have a close connection to that person, this does not really settle the question Which point of view is the general point of view? As Sayre-McCord recognizes, “which group comes within our view depends on the context and character of the person judged.” (“Isn’t Ideal” 210). In other words, what counts as a close connection varies depending on the context. For example, when we evaluate the character of a statesman, we focus on a relatively wide circle of people. When we evaluate the character of a parent, on the other hand, we focus on a relatively narrow circle. We are left with the question, then, Which circle is appropriate for which context? This is not all that different from the earlier question.

[14] This quote is from page 25 of Geoffrey’s Sayre-McCord’s draft paper “Hume on the Artificial Virtues” draft of 7/8/14. Sayre-McCord thinks that this motive underlies all of the artificial virtues, not just justice. This topic was introduced in the last section of Hume 2.

[15] Sayre-McCord writes that “Hume’s argument for introducing the general point of view, and for privileging a certain version of it, parallels the one he offers for introducing the rules of justice, especially in its appeal to mutual interest” (“Isn’t Ideal” 222). Given the parallels between Hume’s discussion of justice and his discussion of moral judgment, it would be surprising if his answer to the question Which point of view is the general point of view? does not parallel his answer to the question How should we distribute property rights? That being said, to my knowledge, Sayre-McCord does not explicitly endorse the claim that a “commitment to conform to general rules established by conventions, given that the conventions are mutually advantageous, and that others are doing their share as well” is the motive that underlies not just justice and the other the artificial virtues but morality as well. Though he does not explicitly endorse this claim, I suspect that he believes it (or at least, it tempted to believe it) because he says the following: “The natural virtues naturally engage approbation in a way that the artificial virtues do not, although the natural virtues no less than the artificial ones count, in the end, as virtues only because they are properly approved of within a conventional system of approbation” (“Isn’t Ideal” 223 footnote 39).

[16] “In preserving society, we make much greater advances in the acquiring possessions, than in the solitary and forlorn condition, which must follow upon violence and an universal licence” (Treatise 3.2.2.13).

[17] “As Hume would have it, introducing moral thought and the general point of view that goes with it is absolutely crucial to a harmonious social life” (“Isn’t Ideal” 215-216).

[18] I suppose that some people deny the claim that welfare is a moral matter. However, anyone who does must accept the following consequence:

In footnote 12 of Hume 2, I considered the case of a Greek slave who is better off economically than he would have been in a state of universal license. Hume, as I said in that footnote, can avoid the unpleasant conclusion that the slave’s bondage is just by pointing out that, once the moral degradation of slavery is taken into account, the slave is worse off than he would have been in a state of universal license. This move, it seems, would not be open to someone who holds that welfare is not a moral matter.

[19] For now note that Hume thinks that, if we want to know whether morality is a good thing, we must look to morality for an answer. He says that “it requires but very little knowledge of human affairs to perceive, that a sense of morals is a principle inherent in the soul, and one of the most powerful that enters into the composition. But this sense must certainly acquire new force, when reflecting on itself, it approves of those principles, from whence it is deriv’d, and finds nothing but what is great and good in its rise and origin.” (T 3.3.6.3)

Sayre-McCord explores this topic in a draft paper called “On a Theory of a Better Moral Theory and a Better Theory of Morality.”